Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

A Punk with Class —

The Morgan Fisher Interview

Morgan Fisher has a long and interesting musical career. He and I were both born in 1950, but 11 months apart. At the ripe old age of 18 his band The Love Affair scored a #1 UK hit “Everlasting Love” (though in typical fashion for the day, neither he nor his bandmates played on the single). He also began experimenting with electronic music between 1968 and 1972, as well as co-producing Allan Holdsworth’s debut album. Between 1973 and 1977, he was part of the Third Ear Band for a brief period, joined Mott the Hoople in the Bowie years, and guest appeared on many LPs. In the late 70s Morgan set up his own studio and record label where he released Slow Music and the two oddball Hybrid Kids albums. He played keyboards on Queen’s 1982 European tour and then moved to Japan in the mid 80s. Since then, he has continued to record ambient albums and music for art videos, movies, and television. He has also played with local Japanese bands and began his series of light paintings. This past September, he flew back to the UK to perform with Mick Ronson’s daughter Lisa at her record release party.

by Henry Schneider, Published 2015-11-21

I connected with Morgan on LinkedIn back in April 2015, so I saw that as an opportunity to interview him and further enlighten our readership on his history and recent projects.

I connected with Morgan on LinkedIn back in April 2015, so I saw that as an opportunity to interview him and further enlighten our readership on his history and recent projects.

Nice to virtually meet you, Morgan. I would like to begin this interview by exploring your early years. What was your earliest musical experience?

BBC radio broadcasts of all kinds, very popular in my family until we got a TV in 1958, when I was 8. Before we had our own TV I’d visit our neighbor each Friday at 6 PM to watch and thrill to the first UK R’n’R show, Six-Five Special.

If the Spanish Inquisition came to your house and demanded that you give them a description of the music you make, what would you say?

Instant composing – which means improvising with attentiveness, not flailing-around improvisation.

Would you please expand on what you mean by improvising with attentiveness? Some examples? Who in your opinion excels at this? In contrast what music in your opinion is characterized by flailing around improv? Isn’t all good improvisation actually improv with attentiveness?

Five questions in one! OK, here goes...

“Improv” aka “Free Jazz” as a genre I find tends to avoid: 1. Melody, 2. Harmony, 3. Rhythm. So it is not really free at all, and can hardly be called music. It is more like catharsis. All very well in its place. I used to find it thrilling, but now it just doesn’t suit me. It’s a matter of taste, I suppose. I’m not trolling so don’t flame me, please!

A second kind of improv is improv on a theme – which is what much of jazz is. Also much Indian music. This can be very creative in the right hands. But there is always that theme that you have to come back to, so it feels rather like a kite on a string – it can never escape from the base.

The third kind of improv, where you really can fly free, is starting with no theme, no plan at all. And not just throwing noises out and seeing what happens – I’m thinking more about playing in a contemplative way, almost praying for the Muse to inspire you then and there, creating a kind of sacred space for something to manifest. At its best it can be instant composing, rather like an artist, having the guts to face the blank page and create not chaos, but beauty, and new every time. This is probably what Bach and Mozart did, in an era before music got so compartmentalized into written versus improv. Keith Jarrett is a known exponent of this approach. It is certainly much easier to do as a soloist. Wayne Shorter now has a band nicely called Without a Net who specialize in group improv. None of us improvisers are totally free; we all have our personalities, habits, favorite licks, etc. But it is an ideal I like to strive for, where one note can lead to the next, without me getting in the way or forcing a sequence onto it. I find that melodies and phrases created (or “received”) in this way usually do not repeat, but continue to flow and change and develop, resulting in some kind of extended musical story that can last for over an hour and end naturally. I sometimes trick myself out of my habits by setting the keyboards and effects up differently every time (so I’m not 100% sure what exactly will happen when I play a note), or using drum machines whose pattern and tempo I don’t exactly know, so it will shove me in a new direction if I’m ever at a creative block. I have to do it in front of an audience so I’m “put on the spot” – and I have to maintain the attitude that there are no mistakes, only new avenues to explore, right now, in this moment.

What music do you love to listen to?

Frankly, birds singing and the sound of waves are the best for me. Then I have a few albums that have stayed with me for decades and never lose their deliciousness: Gabor Szabo, Chico Hamilton Quintet, 60s soundtracks from French movies by Tati and Vigo, etc.

What music do you hate?

Sentimental country music; enka (Japanese version of same); boy bands, girl bands, etc.

If you could cover one song, what would that song be?

Only one? Not fair! OK, “Alfie” (Bacharach/David, from the film of the same name).

“Alfie” is a surprising choice for a cover. What is it about this song that resonates with you?

Well, in spite of my technical / experimental interests, I am a heart-oriented person, and this song expresses heart and love in the highest sophisticated subtle way that Burt Bacharach is so skilled at – so it satisfies me on all counts!

What was your most memorable experience in a live performance?

Only one? Not fair! Probably my first gig with Mott the Hoople (which was also my first US gig) on July 27, 1973 at the Aragon Ballroom, Chicago. The memorableness began with the opening band, the jaw-dropping, amazing Joe Walsh and Barnstorm at the peak of their game. Followed the very next day by two more support bands at their peak: New York Dolls and Dr. Hook and The Medicine Show! Talk about getting thrown in at the deep end of the USA at its finest!

Interesting experience with your first US tour. That was quite a broad spectrum of musical styles and genres in three days! I remember seeing Mott the Hoople live in Port Chester, NY, in 1970. They gave one hell of a show. I always thought that they were unfairly criticized as being too derivative. How did you become a band member?

Simply by answering their ad in Melody Maker when I was out of work. I didn’t know the band’s music much at all until then. It was mainly the attraction of a forthcoming US tour that made me apply for it, as I’d never been there before. Their original organist had left and they needed one, especially as Ian Hunter wanted to play less piano live, and go up front with his guitar. Wise move, for both of us!

Would you please relate a mishap or triumph when in the studio recording?

Would you please relate a mishap or triumph when in the studio recording?

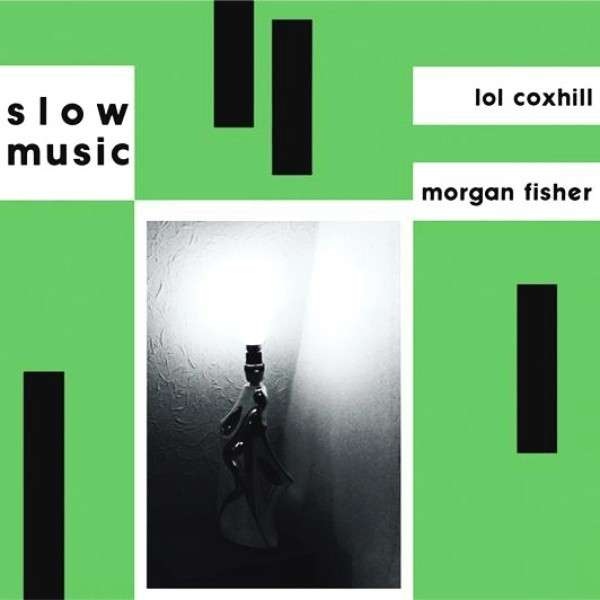

Recording Slow Music, my first ambient album in my first home studio in Notting Hill Gate in 1980. I recorded soprano sax supremo Lol Coxhill playing a long variation on Handel’s Largo. I then slowed it down to half speed and he improvised unerringly over that. I then spent two weeks looping, layering, editing and processing the recording, resulting in the final album, much of which sounds nothing like a saxophone. A slow-paced, calm, deep triumph!

When you recorded Slow Music, did you have to resort to cutting and splicing tape? Or had technology advanced enough by then to allow you to create digital loops? What challenges did you face at that time in the recording studio?

It was 1980, so no samplers yet, except for the hugely expensive Fairlight. I spent two weeks laboriously cutting and splicing meticulously-measured tape loops all day! Like making a quilt. So the main challenge was – how many hours do I spend assembling a sequence which may turn out to sound like rubbish? Luckily, I seemed to make the right decisions most of the time. For mixing the title track (about 20 minutes long) I dubbed numerous loops onto all the tracks of an 8-track machine, then played it back through a long tape delay system, fading the tracks in and out as I pleased, to create varying layers of repeating, fading sounds. It was a nail-biting experience, but I got it in one take! And of course Lol Coxhill’s soprano sax playing for that album was a tour-de-force (in terms of subtlety and accuracy, rather than volume).

What is the most unusual instrument you either play, wish you could play, or like to listen to?

What is the most unusual instrument you either play, wish you could play, or like to listen to?

Play: A 50s Ondioline (French tube-based monophonic synthesizer in an art deco wooden cabinet)

Wish I could play: Uillean pipes

Listen to: I like to listen to: an ensemble of Ondes Martenots (expensive predecessor of the Ondioline).

Can you describe what an Ondioline sounds like? There were so many different custom built synths before the Moog came along. I was first introduced to electronic music in junior high school by our music teacher. He played recordings from the RCA lab. I was probably the only student in the class who fell in love with electronic music. Though those recordings were quite sterile and academic.

The Ondioline was made (by Frenchman Georges Jenny) in the 40s to be a cheaper, more versatile version of the expensive Ondes Martenot, one of the first electronic instruments ever made (soon after the Theremin). It is smaller and more portable than the Ondes, but has several filters which allow it to do what it was made for – emulate the instruments of the orchestra. In the hands of a good player it is remarkably authentic and warm and expressive, partly due to its fingertip-controlled touch vibrato. Not at all sterile or academic! One such player is Jean-Jacques Perrey (now 86) who was the original salesman of the Ondioline. You can hear his 1950’s demo here:

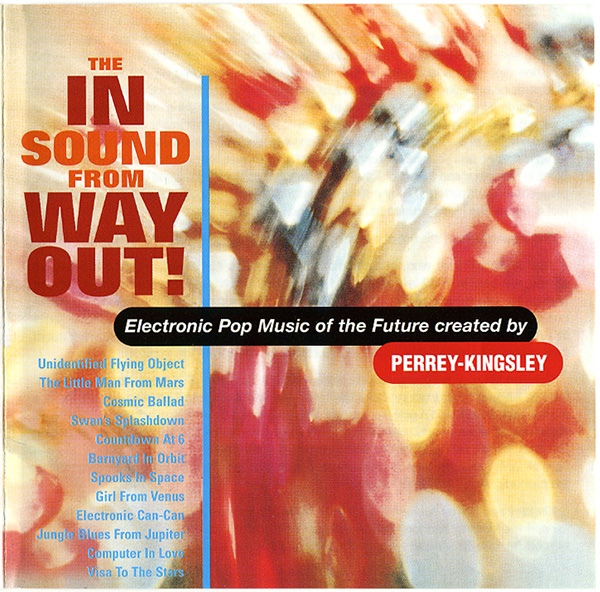

Through his excellent performances on the Ondioline, he attracted the attention and support of such stars as Jean Cocteau and Edith Piaf, leading to him playing the instrument in the USA for Walt Disney and Salvador Dali! Later on he made one of the first Moog pop albums – The In Sound from Way Out! as Perrey and Kingsley.

After I purchased a used Ondioline in 2006, he kindly introduced me to a Paris workshop where it was thoroughly refurbished, and personally came there to check it for me, pronouncing it “Comme nouveau!” (like new).

After I purchased a used Ondioline in 2006, he kindly introduced me to a Paris workshop where it was thoroughly refurbished, and personally came there to check it for me, pronouncing it “Comme nouveau!” (like new).

The first time I had heard an Ondioline was in about 1970 on a Blood, Sweat and Tears album. I had no idea it was electronic – it sounded rather like an Indian-style oboe. Player Al Kooper used it to great dramatic effect on that album and also on his Super Session and solo albums.

Being a fan of Al Kooper and Super Session, I now know exactly what your are talking about. I love “His Holy Modal Majesty.” I heard that song on the radio in 1968 and it motivated me to buy the LP.

That Kooper track is a classic, will listen to it now! When I met him here a few years back he surprised me by saying he never owned an Ondioline – just found it in a studio and borrowed it. That way, he avoided a lot of hassle and expense (as I know too well!).

What is your favorite of all your recordings?

Only one? Not fair! OK, the aforementioned Slow Music. And Saturday Gig – the last single by Mott the Hoople.

What was your most bizarre experience playing in a band?

What was your most bizarre experience playing in a band?

Playing on the Isle of Man with Mott the Hoople. The hall piano was so bad, dreadfully out of tune, that at the end of the show I decided to express my opinion with a gesture – shoving it to the edge of the stage, where I expected its front foot to slip off and leave it stranded there like a beached whale. It actually flipped up vertically, really fast, and stayed poised up there, without, luckily, killing any of the tuxedo’d bouncers who stood along the front of the stage.

If you had a time machine and could travel to any time or place to make music, where would you go and why?

No hesitation: Paris, in the 20s, to jam with Erik Satie and hang out with Picasso, Diaghilev, Cocteau, and Man Ray. Surrealism, Dada – kind of punk with class.

What is it like performing with a younger generation of musicians?

I feel as young if not younger than they are, as I am often far more flexible, versatile and adventurous than those I play with (wink!). For example, after playing several times with the retro-rock Japanese girl trio called the 5678s (who Quentin Tarantino and John Waters adore – they played two songs in Kill Bill) – I have now received the honorable title of “No. 9.”

How have your musical tastes changed over the years?

They have lightened. That means that while I still have great interest in experimental, avant-garde, cutting edge music, I veer more towards works that uplift me rather than drag me into the dark morbid worlds in which I used to enjoy immersing myself. You can clearly hear the difference between the two Miniatures albums I produced, made in 1980 and 2000 respectively. Each was a collection of pieces no longer than one minute, by a total of 106 artists (!).

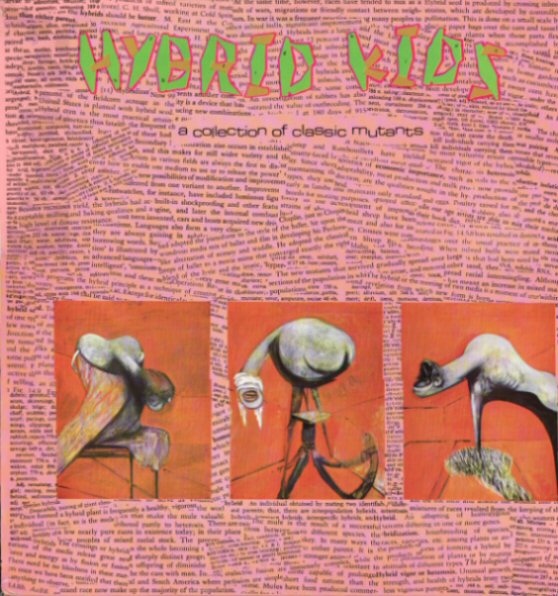

What led you to record the Hybrid Kids albums, which are so different from your other work?

Suddenly feeling utterly free, released from a non-stop decade of playing with name bands for major record labels, trying to get hits. Cherry Red Records gave me carte blanche to do whatever I liked – and I had just created my first low-cost home studio. As a completely self-contained musician, engineer, producer, cover designer, etc., my creativity went swiftly into top gear. I needed to cram as many ideas as I could into each album. I was inspired by the recent punk explosion but influenced by the myriad varieties of music I had always enjoyed. Tremendous fun!

The Hybrid Kids albums are so bizarre, especially the second, Claws. When I lived in Houston, TX there was an import show on public radio every Sunday night. That show introduced me to a wide variety of new and unusual music, including your irreverent cover of “We Three Kings.” Those Hybrid Kids albums were so creative, but must have been quite a challenge to compose and record. What do you remember about that experience?

Basically, utter joy and playfulness. At last I had my own home studio and enough gear to record my own album there. I played not only keyboards but guitar, bass, percussion, and sang and recorded and mixed the whole album at a cost of £25 (the cost of the tape). After a morning meditation and walk in Hyde Park, I’d put in a full day’s recording then go drinking with friends in local wine bars. One of the most enjoyable times in my life and a great self-learning program – the subjects being punk, dub, reggae, ambient, mixing, singing, etc. I certainly don’t remember any challenges other than “let’s see how much I can do with the limited means at my disposal – let’s really push the envelope.” So I did! The main idea was to give songs utterly incongruous arrangements: the Sex Pistols like a Pinky & Perky puppet show, Perry Como like Devo, “Macarthur Park” like a ska band, etc. On the second album (all Christmas songs) it got a bit less jokey and took on a darker, “art-punk” or “post-punk” mood. But never heavy, I’m just not that kind of guy (wink!).

What circumstances led you from England to Japan?

What circumstances led you from England to Japan?

Well, after my two-year burst of creativity I decided the next step was to visit (and try living in) various countries: India, Belgium, the US, traveling alone, at a much slower pace than I had done as a touring rocker. Within a couple of years I realized that the East was calling to me, so I answered the call and started a new life, from nothing, in Tokyo, where I still live 30 years on.

How did you transition from music to art?

Both activities were always a part of my life but music was the one that took over, since my first band’s #1 hit in 1968. I was always interested in art and visited museums worldwide and read art books avidly. I didn’t find my direction until about 20 years ago when I almost accidentally happened upon the technique I use now, called “light painting.” In my case, this means moving the camera during long exposures, rather than moving the light, which I consider to be far more limiting. It has evolved gradually from a hobby to a passion and a vocation. I exhibit both in Japan and abroad and am always looking for more opportunities to do so. In addition, I usually project my art while I perform music, so the two go hand-in-hand, quite happily.

Most photos courtesy of Morgan Fisher, from his website. See links below for more images and information.

Filed under: Interviews

Related artist(s): Morgan Fisher, Lol Coxhill

More info

http://www.morgan-fisher.com/mo-gallery.html

http://www.morgan-fisher.com/biography.html

http://www.youtube.com/user/morganfisherart/videos

http://www.morgan-fisher.com

http://www.morganfisherart.com

http://soundcloud.com/morgan-fisher

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Review: Pando Pando - Pando Pando

Published 2024-04-18 - Review: Steve Roach - Reflections in Repose

Published 2024-04-17 - Listen and discover: Mono Takes an Oath to Be Epic

Published 2024-04-17 - Review: I.P.A. - Grimsta

Published 2024-04-16 - Review: Ubermodo - So Very Far from Home

Published 2024-04-15 - Review: Välvē - Tiny Pilots

Published 2024-04-14 - Review: Sultans of String - Walking Through the Fire

Published 2024-04-13 - Review: Shiver - Shiver Meets Matthew Bourne Volume 1 & Volume 2

Published 2024-04-12 - Release: Full Earth - Cloud Sculptors

Updated 2024-04-11 16:21:34 - Artist: Full Earth

Updated 2024-04-11 16:20:18 - Review: Deorbit - Retrogradient

Published 2024-04-11 - Review: Ellesmere - Stranger Skies

Published 2024-04-10 - Artist: Edge

Updated 2024-04-09 17:02:40 - Release: Neil Ardley - Harmony of the Spheres

Updated 2024-04-09 16:56:49 - Release: Neil Ardley - A Symphony of Amaranths

Updated 2024-04-09 16:54:58 - Artist: Neil Ardley

Updated 2024-04-09 16:44:43 - Release: Zodiac - Disco Alliance / Music in the Universe

Updated 2024-04-09 16:16:54 - Artist: Zodiac

Updated 2024-04-09 16:09:02 - Review: Rudy Adrian - Reflections on a Moonlit Lake

Published 2024-04-09